Rachel's Democracy & Health News #955

Thursday, April 17, 2008

From: Rachel's Democracy & Health News ...............[This story printer-friendly]

April 17, 2008

LIVING ABOVE THE LINE

[Rachel's introduction: Our legal and economic systems are based on the assumption that economic growth always provides more benefits than harms. But now that we have exceeded many of Earth's ecological limits, that basic assumption no longer holds true. The implications are profound.]

By Peter Montague

I know it's not fashionable to talk about limits. Nobody likes limits. But anyone who's paying attention knows that the Earth has definite limits. It's a tiny place, really. (If the Earth were a peach, then the part of it we inhabit -- the biosphere -- would be the fuzz on the peach.)

About six months ago, the United Nations Environment Programme's fourth Global Environmental Outlook Report (GEO-4) concluded that we humans presently require 22 acres per person to support our global average lifestyle -- but, the report said, Earth has only 15 acres per person available.

In other words, we have already exceeded the Earth's "carrying capacity" -- it's capacity to "carry" (or support) 6 billion humans. And the human enterprise is poised for a massive spurt of economic and population growth -- expected to raise our numbers to 9 billion by roughly mid-century and to double the size of the human economy every 23 years.

This is why the surface of the Earth is getting warmer, chemical contamination is rife, fresh water is in short supply, and there are food riots occurring or threatening to occur in about 40 countries. Given the way we live now, there's not enough space on earth to provide land for the food and minerals we require, plus places to absorb our wastes.

The situation is serious. In 2005, when the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment was published, the directors of that authoritative study said, "At the heart of this assessment is a stark warning. Human activity is putting such strain on the natural functions of Earth that the ability of the planet's ecosystems to sustain future generations can no longer be taken for granted."

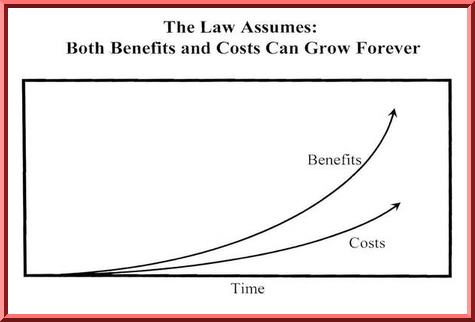

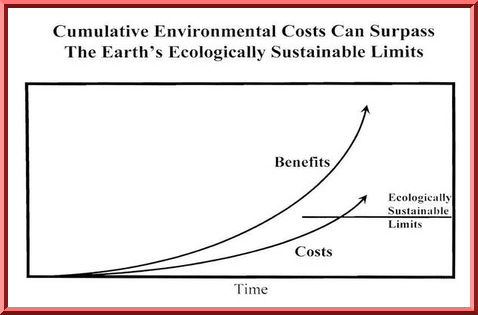

Unfortunately the U.S. legal and economic systems are premised on the idea that everything can grow without limit -- and everyone else's legal and economic systems seem to rest on similar assumptions. Attorney and scientist Joseph H. Guth** shows this in two simple graphs.

Here's the first one:

In this graph, Joe Guth shows the two basic assumptions that underpin our present legal and economic systems (and the regulatory system they have spawned). First, the system is premised on the assumption that economic growth is always good -- which is to say, the benefits will always be larger than the costs. (Joe Guth wrote about this in more detail in Rachel's #846.) Yes, the system acknowledges that people are being harmed and that the earth is being stressed by "development" -- but overall the system assumes that benefits always outweigh costs.

This is why it is almost impossible to beat polluters in court -- the legal system assumes that the polluter is creating more good than harm and it is up to you, the plaintiff, to prove otherwise. If you can prove to a near certainty that the costs of an activity outweigh the benefits, you've got a fighting chance that the judge will make the polluter pay a fine or perhaps even cut back the pollution a bit. But notice that the burden of proof rests on you to prove that the harms outweigh the benefits. If there is any real doubt or uncertainty, the polluter wins automatically (the polluter gets the benefit of the doubt).

Secondly, both the legal system and the economic system assume that costs can grow forever without limit. That's what Graph 1 shows. Neither the economic system nor the legal system recognize that the Earth is finite and that we've already run out of space to support ourselves in the style to which we have become accustomed.

In the law, there are no built-in limits -- nor even any built-in way to recognize limits or even to recognize the need for limits -- and anyone who wants to impose limits bears the burden of proving that limits are necessary and reasonable. Without compelling proof, growth proceeds unchecked. Growth gets the benefit of the doubt.

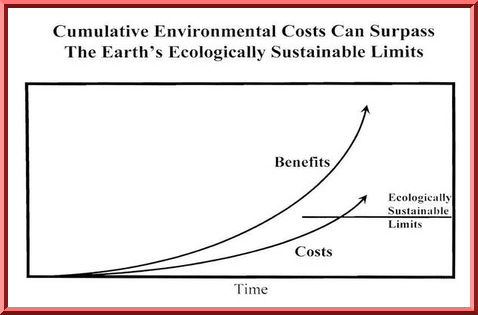

Now let's look at Graph 2.

Here we see a horizontal line that represents the ecological limits of the Earth. According to the GEO 4 report and the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, we are already living above this line -- and so about 2 billion people have run out of necessities (water and food), not to mention housing, education, health care, and the other basics of a decent life.

You could say that the horizontal line represents the "precautionary principle." In many cases, we don't know exactly where the limits of the biosphere lie. But when we exceed them, we usually learn about it the hard way -- ocean fisheries stop producing fish, for example, or the temperature of the planet begins to rise and storms grow more frequent and more destructive, or industrial poisons begin to be measured in human babies' first poop (which is called meconium). These are all unmistakable signs that we have exceeded earth's carrying capacity (sometimes called "assimilative capacity") and that our cumulative costs have risen above the horizontal line in Joe Guth's second graph.

Some Growth is Good

Economic growth is needed in poor countries, so they can begin to live a better life. They need roads, power plants and ports. They need to achieve a middle-class lifestyle so they can afford real social security programs instead of relying on large numbers of children as their only old age insurance. (This is the answer to "the population problem" -- middle class people naturally want small families, so we need to raise everyone's standard of living so they need and want fewer children.)

But growth in the global South will require us to cut back in the overdeveloped global North. The wealthy countries need to operate their economies substantially below that horizontal line in Joe Guth's second graph, to make space for needed growth in the global South.

To do that, our legal system needs to develop some new assumptions: traditional economic growth can no longer be assumed to provide net benefits. Arguably, growth in the global North is already creating more harm than good and the law needs to reflect that. The burden should now be placed on those who aim to enlarge the human "ecological footprint" -- they should have to show that the benefits will outweigh the costs. And the burden should be on them to offer persuasive evidence; if there's substantial doubt or uncertainty, then the law should assume that expanding the human ecological footprint is a net detriment, to be prevented. (This is what it means to "reverse the burden of proof.")

When the cumulative costs of many, many small projects add up to a threatened planet, it is time to take into consideration the "cumulative impacts" of traditional growth and development. And since this is hard to do, the precautionary principle becomes our standard decision rule: when essential data are missing or the science is uncertain, give the benefit of the doubt to nature and to human health.

When you're living above the line -- as abundant evidence suggests we are now doing -- then our task is to re-examine everything we are doing and choose the least harmful ways. Eat lower on the food chain, travel less, build fewer McMansions, revive mass transit, revitalize our cities, shift to less destructive ways of farming, and so on. This need not feel painful or restrictive -- if we take it as an exciting opportunity to find our right livelihoods, to discover and create sustainable ways of being on the planet. As we know from the important not-for-profit sector of our economy, endless growth is not essential for creating plenty of good jobs.

One thing is certain: the earth is our only home and we'd had better take care of it or we're goners. Continuing to live above the line is a recipe not only for increasing pain and misery, but eventually for extinction.

=========================================================

Additional reading:

James Gustave Speth, The Bridge at the Edge of the World (Yale University Press, 2008).

Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005)

United Nations Environment Programme's fourth Global Environmental Outlook Report (GEO-4)

** Joseph H. Guth, J.D., Ph.D, is Legal Director of the Science and Environmental Health Network (SEHN). He is a member of the New York State Bar, has a law degree from New York University, a Ph.D. in biochemistry from the University of Wisconsin (Madison), and an undergraduate degree in biochemistry from the University of California, Berkeley.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

From: Greenwire ..........................................[This story printer-friendly]

April 14, 2008

POTENTIALLY DANGEROUS SLUDGE USED IN LEAD-POISONING TEST

[Rachel's introduction: In the late 1990s, government-funded studies in poor, black neighborhoods in Baltimore and East St. Louis, Ill., traded food coupons and free lawns in exchange for permission to spread sewage sludge on their yards.]

Scientists conducting research supported by federal grants spread sewage sludge made from human and industrial wastes on yards in poor, black neighborhoods to test whether the fertilizer could protect children in the area from lead poisoning in the soil. Families in the areas were assured the sludge was safe and were never told about its potentially harmful ingredients.

In the late 1990s, government-funded studies in poor, black neighborhoods in Baltimore and East St. Louis, Ill., traded food coupons and free lawns in exchange for permission to spread sewage sludge on their yards. Researchers said the sludge helped put children less at risk of brain damage from lead, a highly toxic element once used in gasoline and paint that children could ingest as it flaked off walls in their houses.

The researchers said phosphate and iron in the sludge could bind to lead and other hazardous metals, allowing the combination to pass safely through a child's body if eaten.

Rufus Chaney, an Agriculture Department research agronomist who co- wrote the study that took place in Baltimore, said the researchers told the families about lead hazards and told the people that the sludge, Orgro fertilizer, was store-bought and safe. He said the researchers did not, however, inform the families about some studies that indicate safety disputes and health complaints over sludge.

No one can say exactly what is in sludge because of its dynamic nature, containing primarily human excrement but also anything else flushed down a toilet or poured into a drain: industrial chemicals, drugs, personal care products, flame retardants and other byproducts of modern civilization.

Soil chemist Murray McBride, director of the Cornell Waste Management Institute, said he agrees with the researchers about sludge's ability to bind with lead in soil, but he does not assume that it is necessarily safe.

"If you're not telling them what kinds of chemicals could be in there, how could they even make an informed decision? If you're telling them it's absolutely safe, then it's not ethical," McBride said. "In many relatively wealthy people's neighborhoods, I would think that people would research this a little and see a problem and raise a red flag."

Although government documents outlining the research grants do not list any names of individuals participating in the study for privacy concerns, it also does not indicate any medical follow-up.

"The study did not test children or other family members living in the homes," said Joann Rodgers, a spokeswoman for Johns Hopkins, which is affiliated with the Kennedy Krieger Institute that conducted the research in Baltimore (Heilprin/Vineys, AP/San Francisco Chronicle online, April 14 and Kevin S. Vineys, AP/San Francisco Chronicle online, April 13). -- KJH

Copyright 1996-2008 E&E Publishing, LLC

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

From: Portland (Or.) Tribune .............................[This story printer-friendly]

April 15, 2008

IS INDUSTRIAL POLLUTION MAKING AMERICA FAT?

[Rachel's introduction: Dr, Bruce Blumberg believes the obesity epidemic actually is due, in part, to industrial pollution -- specifically to low levels of toxic compounds he calls "obesogens."]

By Chris Lydgate

Despite the nagging of diet experts, fitness instructors, public health officials, doctors, nurses and moms, the tide of obesity that has practically engulfed Western civilization over the past two decades shows no sign of reaching its ebb.

In the United States, the percentage of adults who are obese -- defined by the National Institutes of Health as a body-mass index exceeding 30 -- has doubled since 1990, climbing from 12 percent to a whopping 24 percent in 2005, closely tracking Oregon figures, according to the Oregon Health Division.

For the most part, the blame for the obesity epidemic has fallen on diet and exercise, with particular emphasis on familiar evils such as the proliferation of junk food, the advent of the remote control, trans fat, ever-longer commutes and even the disappearance of physical education in schools.

But now some researchers have identified a new suspect: pollution.

Attributing obesity to diet and exercise is "practically scientific dogma at this point," says Bruce Blumberg, associate professor of developmental and cell biology at UC Irvine. But, he continues, "diet and exercise are simply not adequate to explain the explosion of obesity in Western countries."

Instead, Blumberg believes the obesity epidemic actually is due, in part, to industrial pollution -- specifically to low levels of toxic compounds he calls "obesogens."

Just as exposure to carcinogens can trigger cancer, Blumberg and other researchers say exposure to obesogens can trigger a dramatic increase in the amount of fat produced in a person's body, leading to excess weight and obesity.

The precise mechanism by which these obesogens operate remains dimly understood. They belong to a class of compounds known as "endocrine disrupters" because they block or pervert the operation of the hormones that govern crucial biological processes such as growth, reproduction, sexual development and behavior.

Five years ago, Blumberg was studying the biological effects of various marine pollutants -- in particular, tributyl tin, or TBT, a pesticide notorious for its toxic properties, such as bizarre mutations in the shells of mollusks and the sex organs of sea snails.

Blumberg and his co-workers exposed female frogs to extremely low levels of TBT; as expected, TBT did indeed cause sexual mutation among frogs. But what was really striking, he says, was that the hapless amphibians got fat -- really fat.

"To be honest, I will have to say we stumbled on this," he says.

Tiny doses had a big effect

Although most of the research on endocrine disrupters has focused on their potential effects on sexual development, fat production also is regulated by the hormone system and is, theoretically at least, just as susceptible to disruption.

Blumberg injected mice with TBT and observed similar results: fat rodents. Even more significant, the compound triggered obesity in ridiculously min-uscule quantities. In fact, Blumberg and his colleagues demonstrated effects from TBT at 27 parts per billion -- the rough equivalent of 4 tablespoons in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

Blumberg concluded that the fattening effects of TBT and a group of similar compounds known as organotins are so profound that even trace amounts could trigger an increase in weight. "The introduction of organotins is likely to be a contributing factor to the obesity epidemic," Blumberg says.

Toxicology experts concur that some compounds are so potent that they can indeed trigger changes at minute concentrations, at least in the test tube.

"It sounds absurd, but it's not inconsistent with what we see in the lab," says Fred Berman, director of the Toxicology Information Center at the Center for Research on Occupational and Environmental Toxicology at Oregon Health & Science University.

Organotins are everywhere

The disruptive effects of organotins stem from their propensity to stimulate a particular hormone receptor that plays a key role in maintaining the body's metabolism, in effect telling the body which kind of cells are in short supply and need to be grown.

Organotins somehow encourage that receptor to manufacture fat cells -- which in turn promotes that ominous abdominal bulge feared by statisticians and movie stars alike.

Organotins first came into widespread use in the 1960s in the shipbuilding industry, where they were mixed with paint to deter barnacles and mollusks from accumulating on the hulls of ships.

They also have been used as soil fungicides for crops such as nuts, potatoes, rice and celery; as "slimicide" to clean up the goop that accumulates in underground water wells; and in the manufacture of polyvinyl chloride, or PVC, a hard plastic found in drainpipes, vinyl flooring, window frames and hundreds of other places.

These widespread uses suggest several possible routes of human exposure, Blumberg says. Organotins may contaminate crops, seep into wells or leach into drinking water from PVC pipes.

Link to obesity stays unclear

It is worth pointing out, however, that little research has been conducted into actual levels of organotins in the average household.

Moreover, many basic questions about the link between organotins and fat remain unexplored -- for example, whether people who might encounter high levels of organotins as a result of their occupation, such as farmworkers or shipyard workers, suffer higher rates of obesity.

The pernicious effects of organotins on the marine environment are well-established, and they now are banned as anti-barnacle agents.

Nonetheless, they continue to be used in agriculture and in the manufacture of plastics. "At my house, we minimize the use of plastic to store food," Blumberg says. "We use glass or stainless steel instead, and in general we try to eat fresh, local, organic food with as little packaging as possible."

OHSU's Berman reckons that Blumberg's research raises "a real concern" about the role of organotins and other possible pollutants in the obesity epidemic. "We need to be looking at this," he says. "But we don't know for sure. We need to do more studies to see if there is a real effect in the real world."

Blumberg is careful to note that obesity is a complex phenomenon stemming from many factors, and that obesogens probably are only part of the story.

In addition, he points out that people who are exposed to obesogens are not doomed to a lifetime of corpulence -- they simply have to work harder than others to shed weight.

chrislydgate@portlandtribune.com

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

From: Good Times Magazine ................................[This story printer-friendly]

March 19, 2008

MESSAGE IN A BOTTLE

[Rachel's introduction: Trash twice the size of the continental United States is collecting in the North Pacific, but here's the kicker: most of it is made to last forever.]

By Amanda Martinez

One sunny day 10 years ago, Captain Charles Moore was sailing home from a yacht race in Hawaii when he steered his boat off-course in search of a little adventure in the North Pacific. Heading north in his 50-foot catamaran, Alguita, Moore wanted to graze the lower Eastern corner of a rarely sailed region, the North Pacific subtropical gyre, before making his way home to Long Beach, California.

The most remarkable characteristic of the gyre, a 10-million-square- foot, clockwise-churning vortex of four converging ocean currents, was supposed to be its unique weather pattern. It's a high-pressure area, meaning that warm air hovers over it. The air is still. There's no wind. Picture an immense oceanic desert. Frustrated sailors long ago christened the area "the doldrums" and avoided it, as do predatory fish who find no prey within its calm, nutrient-lean depths. "It almost looks like an oil slick, or like a mirror. It's really beautiful, the phenomena of a very smooth ocean," says researcher Dr. Marcus Eriksen.

But as Moore ventured into the gyre, his fascination with weather patterns gave way to a different reaction -- alarm. In this most remote part of the ocean, his expectation of the pristine was met by blight.

A vast array of trash -- bottle caps, plastic bottles, fishing floats, wrappers, plastic bags and fragments, many tiny plastic fragments -- stretched before Moore as far as the eye could see. His alarm turned to shock. It took him a week to sail through the gyre, the debris surrounding his boat the entire time.

Dr. Marcus Eriksen considers his first encounter with the gyre to have occurred on the beach in 2001 while teaching bird biology to high school students. This particular beach belonged to Midway Atoll, the last island of the Hawaiian Archipelago. "I noticed the hundreds of carcasses of Laysan albatrosses," says Eriksen. "Every single one had a handful of plastic inside its rib cage." He quickly made the connection between the plastic pieces and their stark resemblance in ocean waters to the fish, squid and krill that serve as staples of the foraging albatross' diet. "I knew there was this floating plastic that these birds were consuming," he says. "That got me interested in the issue."

Four years later, Eriksen became director of research and education for the Algalita Marine Research Foundation (AMRF), the nonprofit that Moore founded after discovering the gyre. Together, Moore, whose resume reads like a coming-of-age at sea story -- deck hand, stock tender, able seaman and now captain -- and Eriksen, a Marine who served in the first Gulf War, have made several trips back to the gyre to research the content and extent of its massive pollution and monitor its growth. When not at sea, the two men are working tirelessly to educate the public as to its existence and causes.

So Rubber Duckie, You're the One

By now, you may have heard reports of the enormous "trash patch" forming in the North Pacific gyre, as major news outlets have a two- minute, sound-bite love affair with the gyre's pervasive description.

"It's twice the size of Texas," they say. "It's an incredible, floating, plastic island in the middle of the ocean."

"Twice the size of Texas is inaccurate. I wouldn't use that anymore," says Eriksen, who returned on Feb. 28 from AMRF's latest 4,000-mile research mission, during which he spent a solid four weeks in the gyre, running experiments. "If you want to give folks an idea of the extent of pollution in this gyre, I'd say twice the size of the continental United States is the best way to put it."

THIN PLASTIC SOUP

Plastic and plankton duke it out in a 6:1 ratio in this one-mile trawl sample from the North Pacific Gyre. The "floating plastic island" metaphor, which may very well have been the gyre's one-way ticket to urban legend, is also out. The details of the truth that stand in its wake, however, are much more pernicious. "It's not a plastic patch. There is no island out there," explains Eriksen. But if it's still the salient metaphor you're after, Eriksen is armed with one. "I'd say endless from Hawaii to L.A. is a thin plastic soup. The rope and the netting and the monofilament line, all the fishing gear that's out there, there's a lot of that, we'll call that the noodles.

The vegetables are all the big stuff, like the fishing floats and the plastic bottles. We found a suitcase floating around...big chunks of Styrofoam, tons of bottles, milk crates, fishing crates. I found a laundry basket that had something like 20 fish in it. And when I picked it up, they wouldn't get out of it."

Oceanographers estimate that the amount of trash currently percolating in the gyre weighs in at 3.5 million tons and extends 300 feet beneath the ocean surface. So the question begs to be asked: where is it all coming from? About 20 percent of the debris results from spillage and dumping at sea. High seas and turbulent storms coax entire cargo containers into choppy waters (remember the 80,000 Nike shoes lost from the Hansa Carrier in 1990 and the 29,000 "rubber duckies" that, in a moment of grave irony, were washed overboard from their cargo ship in 1992?), passenger vessels dispose of waste in what appears to be a conveniently unaccountable location, and both commercial and recreational fishing vessels lose their equipment or simply toss it overboard to evade costly disposal fees at port. As for the other 80 percent, that's coming from land -- litter that's left in piles on the beach, overflowing garbage cans, sloppy trash transport and industries' lax disposal methods. Let's say, for instance, a plastic bottle is discarded on the street here in Santa Cruz. Aided by wind, it finds its way into one of the gaping storm drains that line the streets, the ones subsequently posted with the warning "no dumping, drains straight to Bay." If you ever harbored any doubts as to whether these signs make good on their promise, the answer is yes. "It's simply gravity flows," explains Bill Kocher, director of the City of Santa Cruz Water Department. "There are underground pipes, so when something goes into an inlet like that, it flows into sort of a concrete basin and there's a pipe that exits that basin. And then it'll just flow from there by gravity, usually to a waterway like a creek before it hits the Bay.

Once in the Bay, our bottle begins about a two-week journey out to sea, where approximately 500 miles off of our shore, it catches a current from the gyre and joins the congregating purgatory of trash gathering at the gyre's core like bubbles amassing in the center of a hot tub. In the ten years since it began monitoring the gyre's trash burden, AMRF estimates that it's increased five-fold. "That's a conservative estimate," says Eriksen.

"We'll know more when we analyze all of the samples from our latest voyage."

Heading for the Breakdown

Oddly enough, the main concern over what is now considered to be the world's largest landfill aren't the facts that it exists at all or is growing at such an alarming rate. It's that the majority of it is plastic. A report issued by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) states that plastics comprise 60 to 80 percent of the ocean's total trash, as well as 90 percent of all floating marine debris.

Why the focus on plastic? Because it's synthetic, so unlike other debris, it doesn't biodegrade. Instead, it photodegrades; UV light from the sun breaks it down into smaller and smaller pieces until you have countless plastic particles, and eventually a fine plastic dust.

Revisiting Eriksen's "soup metaphor," these plastic shards, particles and dust are what he calls the "broth."

"Looking down from the bow of our ship, you could see a very spaced- out confetti of plastic particles," says Eriksen. "A lot of it is microscopic, things are degrading into basically polymer-size molecules, which you really can't see with the lot of it is microscopic, things are degrading into basically polymer- size molecules, which you really can't see with the naked eye." While in the gyre, AMRF researchers use a manta trawl, a super fine mesh net ("it's smaller than the holes in your T-shirt," says Eriksen) to collect samples of seawater in order to measure its concentration of plastic. So far, AMRF's samples have yielded a ratio of six parts plastic to one part plankton -- that's six times as much plastic as plankton in the middle of the ocean.

Pictures Worth 1,000 Statistics

Nowhere have the consequences of the gyre's trash manifested more horrifically than in the effects it has had on marine life. One million seabirds, 100,000 marine animals and numerous fish die each year, either mistaking debris for food or becoming entangled within it and drowning. A report from the UNEP states that these harmful effects have impacted 86 percent of all sea turtles, 44 percent of all seabird species and 43 percent of all marine mammals.

Clinical statistics aside, pictures evoke a sincere moral indignation -- a sea lion is choked by a plastic ring carving into the flesh around its neck; monofilament fishing line cuts into the flippers of a sea turtle, drawing blood; even a whale ensnared by nets and gear drags them along behind it, the ropes digging into its back.

It's too large to drown, but it can't hunt and will eventually starve.

According to the National Oceanographic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), 90 percent of Laysan albatross chick carcasses contain plastic. The chicks don't make it off the beach; it's their parents that fly thousands of miles out over the gyre, to bring back faux- nourishment in the form of pieces of plastic and plastic bag that in ghosting the water's surface look identical to krill and squid. The chicks can't digest it and die within days.

Eriksen mentions the ongoing partnership AMRF has with NOAA in which it helps them to tag ghost nets. "They're these mountains of derelict fishing gear abandoned in the ocean," Eriksen explains. Fish and animals get trapped within them, they can't hunt and/or they can't breathe and so they die. If AMRF finds one, they attach a satellite buoy to it so NOAA can track and remove it. "They're too big for us," he says. "This last time, we actually found a two-and-a-half ton net floating around, just full of fish under it. So we put a buoy on it."

But while the effects of the gyre's plastic debris on marine life have been severe and immediate, scientists are accruing evidence that its repercussions for humans, at the genetic level, may be even worse in the long run.

Et tu, Nalgene?

Simply put, plastic is made from petroleum-based synthetic polymers to which chemicals are added to achieve certain characteristics, like inflammability and malleability. These chemical additives certainly aren't the kind of thing you'd want to ingest by any means. In fact, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines them as persistent organic pollutants (POP) or toxins that "persist in the environment for long periods and biomagnify as they move up the food chain," and classifies many of them as known carcinogens. They do, however, come into awfully close contact with our food and beverages, as well as items we use everyday, and as such, our ingestion of them has become unavoidable.

Take phthalates for instance -- deemed as a "known human carcinogen" by the World Health Organization, it's added to polyvinyl chloride (PVC) to make products soft and supple. Ever notice how oily the inside of a bag of potato chips gets? It turns out that oil would eat away at the bag if not being prevented from doing so by a film of PVC. The chemical, also found in shrink wrap, cosmetics and toys, was banned by Gov. Schwarzenegger last August in toys manufactured for children aged 3 and under, and on Feb. 21, AB 2505, a bill that would phase out PVC packaging, was introduced to the California legislature. Keep in mind that the use of PVC was phased in in 1926.

Then there's bisphenol A (BPA), which, as an additive to polycarbonates, is commonly found in dental sealants, the resin linings of food and drink cans and, most ubiquitously, plastic bottles, from single-use water bottles to trusty Nalgene canteens to baby bottles. The chemical, of which six billion pounds is produced annually, is increasingly being identified in scientific studies as a hormone disrupter that mimics estrogen and leaches into foods and liquids. A Time magazine article published on Feb. 8 casts BPA as a "parents' nightmare" while describing a study in which researchers tested 19 baby bottles bought from the U.S. and Canada. Every single bottle, when heated to 175 degrees F, leached BPA, and while government health and environment agencies in both countries are still declaring the additive to be safe in small amounts, health-oriented stores like Whole Foods and Patagonia have ditched their entire stocks of polycarbonate bottles.

And that's just two on a list of pollutants that are increasingly present in our environment. How do they relate to ocean plastics? The answer is twofold. As plastic breaks down into micro-particles, it not only retains these chemicals, it absorbs more of them, like a sponge.

In a study published in the Nov. 15 issue of Environmental Science and Technology, British researchers at the University of Plymouth reported that when marine worms were exposed to microplastics that contained a high concentration of a specific toxin, the tissues of the worms showed an 80 percent increase in accumulation of the toxin. The study concludes that microplastics have the unique potential to transport pollutants throughout the ocean ecosystem and global environment.

Asking ourselves how many of these ubiquitous pollutants we can actually name, it's worth taking a moment to contemplate our role at the top of the food chain, as well as just how informed we feel as to the contents of our water supply and what ends up on our plates.

Considering the community's vigorous unease with the recent Light Brown Apple Moth aerial spraying, why is there not more outrage?

A Fool's Head in the Sand

The urge to feel overwhelmed at this point is dually noted. An initial swipe at optimism floats the question; "OK, so how do we clean it?"

The short-term answer is a bit of a let down. "There is no way to clean it right now," says Eriksen. Note, this isn't a vote for hopelessness, it's merely an indication of the immense scope of the problem, as well as of the complications involved in addressing it.

For instance, no single country has jurisdiction over the gyre. "Once you get beyond our coastal waters, it's an international zone that no one owns," explains Eriksen, making it a true global issue. As you can then imagine, nations aren't exactly clamoring to claim responsibility for a clean-up strategy that even the scientists and politicians who have been vaguely willing to consider it, lowball as beginning in the billions.

As a result, a common response has been a kind of c'est la vie apathy.

After all, it's been our practice to tacitly designate some areas of this planet for aesthetic preservation, while others seem destined to hide our actions' most deleterious consequences. Maybe the North Pacific subtropical gyre just drew a short straw, so to speak.

Unfortunately, there are four other high-pressure oceanic systems in the South Pacific, North and South Atlantic and Indian Ocean, respectively. Together, estimates the AMRF, these waters comprise 40 percent of the planet's oceans and roughly 25 percent of the Earth's surface. As to the likelihood that trash exists in these waters as well, Eriksen seems certain.

"Oh, it's global," he says. "Everywhere I go, I see trash. I've gone scuba-diving in Vietnam, walking the beaches in Peru, walking across train tracks in Tanzania. Plastics are on every beach I've gone to."

So the out-of-sight, out-of-mind strategy is not going to fly. Another common reaction has been denial. Search the gyre online and you'll find many exasperated posts, demanding "well, where are the satellite pictures?" followed by bold declarations of continued skepticism until such photo-documentation of a true "trash island" is produced. While such a head-in-the-sand strategy might conjure momentary psychological relief, it's ultimately thwarted by such explanations as the fact that the trash is constantly mobile in the gyre's currents, it is often not in large enough clumps to register as a "detectable object" on satellite radar, if you'll recall, it's believed to extend 300 feet below the ocean's surface and considering the scope of the challenge presented by plastic particles that appear no larger than "confetti pieces" when viewed from the deck of a ship, let alone microplastics, our pictures of proof might be better sought through the lens of viewed from the deck of a ship, let alone microplastics, our pictures of proof might be better sought through the lens of an electron microscope.

Thank You for Plasticizing

"The best thing to do now," says Eriksen, "is to adopt the mantra of physicians: 'Do no more harm.' The way you do that is to stop allowing plastic to enter the ocean and the best way to do that is to, as a culture, stop using disposable plastics."

Here, Eriksen makes a crucial distinction. The advent of plastics has been revolutionary in terms of its benefits to society within the last century -- combat helmets, bulletproof vests, lifesaving medical equipment, not to mention its widespread applications in the computer electronics, aerospace, building and transportation industries. But in the last 50 years, and even more so, within the last 20 years, the use of plastic for single-use products and packaging has skyrocketed.

Plastics are now the fastest-growing material in municipal solid waste streams nationwide. One only need visit a grocery store for evidence; while the plastic bags assembled at the checkout counter have garnered the most international attention in recent months, don't fail to notice the rows and rows of foodstuffs encased in plastic in say, the freezer section, the pre-washed salad corner or the wall of pre- packaged deli meats and cheeses. And those are just the food-related plastics.

According to the American Chemistry Council (ACC), the nation's largest chemical and plastic manufacturers, the U.S. has nearly doubled its annual plastic resin production in the last two decades to almost 120 billion pounds in 2007, compared to the just under 60 billion pounds it produced in 1987. The average American is said to consume 185 pounds of plastic each year.

The overwhelming presence of hyper-disposable plastics has led scientists and concerned citizens alike to raise two burning questions: Why have we so vigorously produced products that contain chemicals of which we have no appropriate and/or safe method of disposal? and, why have we created so many products and packaging intended for single-use, yet made to last forever?

"We're a culture of consumption, we're a throw-away society," says Eriksen. "The use of disposable plastics, it has to end, and what's going to be most effective is a ban on those plastics."

Not surprisingly, this isn't anything close to what the billion-dollar plastics industry has in mind. In comments made to both the Associated Press and the San Francisco Chronicle in the last six months, Keith Christman, a senior director of packaging for the ACC, has come out in strong opposition of production being slowed, recommending instead the Council's willingness to help install additional recycling bins on beaches, and even stating that "plastic bags are a very good environmental choice" when viewed in context with the amount of carbon emissions generated by trucks delivering the same amount of paper bags to retailers.

Rocking the Cradle-to-Cradle

While the importance of recycling can't be discounted, putting more recycling bins on the beach is hardly a sufficient antidote to the global plague that is non-essential, hyper-disposable plastics.

According to the EPA, in 2006, only 2.04 million tons of the 29.5 million tons of plastic generated in the U.S. was collected for recycling. That's just under seven percent. And while not to be undervalued, plastic recycling is riddled with caveats; of those seven auspicious, numbered triangles found on so many types of plastic, only those bearing the numbers one (PET) and two (HDPE) can be recycled to any great effect. Thanks to plastic's low melting temperature and pesky additives, recycled plastic often requires a layer of virgin plastic to prevent old toxins from contaminating the new product, which even then can't be trusted as a food container. Plus, new plastic is simply much cheaper to make.

Furthermore, Eriksen argues, the burden of responsibility and consciousness, when it comes to the appropriate use of plastics, can't be borne by the consumer alone. As evidence, he reframes our well- oiled municipal waste management systems in stark contrast to the situation in many third-world countries. "The developed world has given this technology of synthetic materials to the undeveloped world," he says, "and they have no infrastructure to deal with it... We have a disposable global culture, and to have these persistent materials be part of that culture of convenience is not sustainable."

This is why Eriksen's approach to the issue consists of a multi-tiered attack on four fronts: legislation, re-design, research and education.

"There are changes on the horizon," he says, mentioning measures like California AB 2449, research and education. "There are changes on the horizon," he says, mentioning measures like California AB 2449, which went into effect last July and requires large grocery stores and retailers to offer both in-store recycling bins for plastic bags and an affordable option to purchase reusable bags. This is, of course, a baby step in comparison to China's recent nationwide ban on free plastic bags, which will take effect June 1. "One-sixth of the world's population just stopped using plastic bags," says Eriksen. "It's amazing."

Also worth noting is California AB 258, which Gov. Schwarzenegger signed into law last October. The bill established a task force to regulate the release of plastic resin pellets called "nurdles" into the marine environment. More than 250 billion pounds of these pellets, which are the raw materials used to make plastic consumer products, are shipped to factories worldwide via rail tank car each year, and spills are frequent in massive quantity both at sea and on land due to careless industry procedure. A report released by Greenpeace states that at least 70 species of marine animals ingest nurdles, also called "mermaid tears," mistaking them for fish eggs.

On the re-design front, there's promise in biodegradable plastics derived from corn and starch sources that are gradually appearing as alternatives to garbage bags and restaurant take-out utensils. "But we also have to consider zero-waste design technologies," stresses Eriksen, invoking the "cradle-to-cradle" design philosophy championed by green architect and designer William McDonough that envisions the development of goods and services that can be used, recycled and reused without sacrificing material integrity. "We have to transition to that."

And finally, Eriksen reinforces the need for continued research on the effects of plastic pollution and the constant monitoring of debris in the gyre, as well as the push to increase educational outreach. His exact words with regard to education are "pounding the pavement to get the word out," an understatement from a man who, in 2005, shortly before he joined AMRF, built a raft entirely out of plastic bottles and sailed it 2,000 miles down the Mississippi River to bring attention to the issue.

"One thing I came away with from this most recent gyre voyage is a sense of urgency," says Eriksen. "We have to act now. A fivefold increase in ten years, we can't let that happen in another ten."

What can we do?

** Avoid plastic bags and plastic packaging when possible.

** Avoid any packaging when you can. Buy in bulk and bring your own cloth bags when shopping

** Call the 1-800 number of the company that uses plastic packaging (usually listed on the product's package). Give them this web site of an article about plastic pollution. http://www.gtweekly.com/good -- times/message-in-a-bottle-1

** Even better, visit their web site (also listed on the package) and email them this article as a PDF attachment

** Tell them you like their product but encourage them to seek out biodegradable packaging.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

From: InterPress Service .................................[This story printer-friendly]

April 14, 2008

GLOBAL HOT SPOTS OF HUNGER SET TO EXPLODE

[Rachel's introduction: Food shortages and rising prices of food and fuel around the world are triggering political instability that could infect 40 countries.]

By Thalif Deen

UNITED NATIONS -- As food prices continue to escalate worldwide, some of the poorest nations in the developing world are in danger of social and political upheavals.

The unrest, which is likely to spread to nearly 40 countries, has been triggered largely by a sharp increase in the prices of staple commodities, including wheat, rice, sorghum, maize and soybeans, according to the United Nations.

Following last week's food riots in Haiti, which claimed the lives of four people, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has appealed to international donors for urgent assistance to one of the poorest countries in the Caribbean.

A meeting of the world's finance ministers in Washington over the weekend warned that rising food prices were more of a threat to political and social stability than the current crisis in global capital markets.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has singled out six countries with an "exceptional shortfall in aggregate food production and supplies": Lesotho, Somalia, Swaziland, Zimbabwe, Iraq and Moldova.

An additional six countries with "widespread lack of access" to food include Eritrea, Liberia, Mauritania, Sierra Leone, Afghanistan and North Korea.

The steep rise in basic foodstuffs has already sparked demonstrations and/or riots in Egypt, Cameroon, Haiti and Burkina Faso, while an increase in both fuel and food prices has triggered unrest in Indonesia, Ivory Coast, Mauritania, Mozambique and Senegal.

The FAO has also warned of impending political and social unrest, specifically in countries where 50 to 60 percent of a family's income is spent on food.

"If the basic food requirements of vast numbers of the poor remain beyond them, with a broad range of consequences to their well-being, they will probably have no alternative than to make themselves 'heard' by taking to the streets," says Ernest Corea, until recently a senior consultant with the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) at the World Bank.

This has happened in history, and food riots of varying intensity have already taken place in several countries, he told IPS.

It was the U.S. civil rights activist Martin Luther King Jr. who said that "violence is the voice of the unheard", said Corea, co-author of "Revolutionising the Evolution of the CGIAR".

Anuradha Mittal, executive director of the San Francisco-based Oakland Institute, which has done exhaustive studies on issues relating to food trade and agriculture, told IPS that various causes for the current crisis are being cited in policy circles, including increased demand from China, India and other emerging economies.

The high per capita income growth of some of these countries has resulted in changing appetites.

Additionally, she noted, the price increases are also attributed to rising fuel and fertiliser costs, climate change, and the new emphasis on converting crops to biofuels, which are being held responsible for almost half the increase in the consumption of major food crops in 2006-07.

"What is not being mentioned is that in the last few decades liberalisation of agriculture, dismantling of state-run institutions like marketing boards, and specialisation of developing countries in exportable cash crops such as coffee, cocoa, cotton, and even flowers has been encouraged by international financial institutions backed by rich countries like the United States, and also by the European Union," she pointed out.

Mittal said these reforms have driven the poorest countries into a downward spiral. "Removal of tariff barriers has allowed a handful of Northern countries to capture Third World markets by dumping heavily subsidised commodities while undermining local food production," she said.

This has resulted in developing countries turning from net exporters to large importers of food, with a food trade surplus of about 1.0 billion dollars in the 1970s transforming into an 11-billion-dollar deficit in 2001.

She also said the situation has been worsened by the dismantling of marketing boards that kept commodities in a rolling stock to be released in event of a bad harvest, thus protecting both producers and consumers against sharp rises or drops in prices.

Corea blamed the crisis on inadequate investment in agriculture and the sharp decline in official development assistance (ODA) for agricultural development over several years.

Additionally, he said, there were also natural disasters and human- made impediments to agricultural development, which is the basis of food security. He pointed out that 21 of the 37 countries listed by FAO as "food crisis" countries requiring assistance have suffered from floods, droughts, and other adverse weather conditions.

And 20 of them are the scene of continuing, current or recent internal conflicts, civil strife, and large scale internal displacement of people.

Moreover, he said, there has been an increased demand for food as a result of both increased population and increased income.

Additionally, as incomes increase, the pattern of food consumption usually changes. For example, higher income earners tend to consume more meats than the poor. One consequence of this trend, he argued, is that some food stocks are diverted for processing as animal feed.

He also blamed rising food prices on subsidies to U.S. farmers for growing crops for energy, in response to the high price of oil and by- products. In 2008, a third of the country's maize output will be used in the production of ethanol and not for food production. Rising fuel prices have also increased the price of some agricultural inputs like fertiliser, and transport.

The diversion from food to fuel has already been described by some developing nations as "a crime against humanity".

Corea said there is also a lack of major agricultural research breakthroughs at the level of Nobel Laureate Norman Borlaug's research triumphs that led to massive increases of cereal production in Asia and Latin America in the 1960s and 1970s.

Also, there has been inadequate attention to the so-called "orphan" crops -- such as millets, indigenous vegetables, local roots and tubers -- which are not commercially as important as rice, wheat and maize/corn but are essential items in the diet of the poor in 26 of the 37 "food crisis" countries.

Asked if she expects the crisis to escalate, Mittal told IPS: "The situation will get worse if the diagnosis of the problem continues to ignore the underlying causes of this crisis and fails to ask what made developing countries vulnerable in the first place.'

Asked how best the food crisis can be resolved, Mittal identified several measures, both nationally and internationally.

Firstly, it is essential to have safety nets and public distribution systems put in place to prevent widespread hunger.

The poorest countries lacking resources should call for and be provided emergency aid to set up such systems.

And donor countries should commit and provide more aid immediately to support government efforts in poor countries and respond to appeals from the U.N. agencies, she added.

Additionally, development policies should promote consumption and production of local crops raised by small, sustainable farms rather than encouraging poor nations to specialise in cash crops for western markets.

National policies involving the management of stocks and pricing, which limit the volatility of food prices, are vital for protection against such food crisis.

Lastly, she said, there is a need to adopt the principle of food sovereignty by developing countries to protect their poorest farmers and consumers.

Copyright 2008 IPS-Inter Press Service

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

From: Austin (Tex.) American-Statesman ...................[This story printer-friendly]

April 14, 2008

UN CHIEF: FOOD CRISIS IS NOW EMERGENCY

[Rachel's introduction: "The rapidly escalating crisis of food availability around the world has reached emergency proportions," says U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon. At least $500 to $750 million is needed on an emergency basis to help 100 million people avert the danger of starvation.]

By Edith M. Lederer

United Nations -- A rapidly escalating global food crisis has reached emergency proportions and threatens to wipe out seven years of progress in the fight against poverty, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon warned Monday.

He called for short-term emergency measures in many regions to meet urgent food needs and avoid starvation and urged longer-term efforts to significantly increase production of food grains.

The international community needs "to take urgent and concerted action in order to avoid the larger political and security implications of this growing crisis," Ban told international finance and trade officials who came to a U.N. meeting following weekend talks in Washington.

Ban's appeal came as President Bush ordered the release of $200 million in emergency aid to help nations where surging food prices have deepened hunger woes and sparked violent protests. The money will come from a reserve fund known as the Bill Emerson Humanitarian Trust.

White House press secretary Dana Perino said the move will help address the impact of rising commodity prices on U.S. emergency food aid programs and help meet the unanticipated food needs of struggling countries in Africa and elsewhere.

Bush's move came one day after World Bank President Robert Zoellick's appealed to governments to quickly provide the U.N. World Food Program with $500 million in emergency aid that it needs by May 1.

Zoellick said the international community has "to put our money where our mouth is" to deal with rapidly rising food prices that have caused hunger and deadly violence in several countries.

Ban said the recent steep rise in food prices "has already raised the cost of WFP's needs to maintain its current operations from $500 million to $755 million."

WFP, the world's largest humanitarian agency, issued an "extraordinary emergency appeal" for the $500 million last month, saying the money was needed by May 1 to avoid cutting rations to some of the world's most impoverished regions. The Rome-based agency said its funding gap was growing weekly.

"The rapidly escalating crisis of food availability around the world has reached emergency proportions," Ban said.

"The World Bank has estimated that the doubling of food prices over the last three years could push 100 million people in low income countries deeper into poverty," he said.

Ban echoed Zoellick in warning that that the food crisis "could mean seven lost years in the fight against worldwide poverty."

U.N. humanitarian chief John Holmes offered a more cautious assessment.

While it is "a very serious problem which has global ramifications," Holmes said, "I think we should be a little bit careful of being too alarmist about it and suggesting there are mass problems around the corner, or that it's a global emergency we have to solve with every detail tomorrow."

He stressed, however, that the $500 million sought by WFP did not cover potential future needs, including those "that might arise from price rises... or if the number of desperately hungry people in a country doubles."

The United Nations is at a midpoint in its campaign to reduce global poverty and improve living standards of the world's bottom billion people. The Millennium Development Goals, adopted at a U.N. summit in 2000, include cutting extreme poverty in half by 2015.

The World Bank's Development Committee urged both the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund "to provide timely policy and financial support... to countries dealing with negative shocks including from energy and food shortages," said Mexican finance official Ricardo Ochoa, who spoke on behalf of the committee.

IMF Deputy Managing Director Murilo Portugal said emerging markets and developing countries have shown resilience but their growth prospects have moderated and inflation risks have increased.

"For many countries, containing inflation and addressing vulnerabilities will remain a key priority," Portugal said.

Copyright 2008, The Associated Press

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

From: Wall Street Journal (pg. D3) .......................[This story printer-friendly]

April 9, 2008

HEALTH FOOD IS GOING TO THE DOGS -- LITERALLY

[Rachel's introduction: The American Pet Products Manufacturers Association expects Americans to spend about $43.4 billion on their pets in 2008, up from $41.2 billion in 2007. About $16.9 billion of that is expected to be spent on food.]

By Anjali Cordeiro

Consumers have been displaying a hearty appetite for all things healthy, natural and vitamin-infused. Consumer companies are pushing that trend a step further, right into the heart of the canine world.

Cott Corp., a maker of private-label sodas for human consumption, is one of the latest companies taking the health-and-wellness craze to the animal kingdom. Cott is rolling out a line of vitamin-infused beverages for dogs, not unlike the enhanced juices and drinks for humans lining grocery and convenience-store shelves.

"This is our first foray into the pet industry," Cott spokeswoman Lucia Ross said. "The same way the trend is healthier food and beverages for people, we believe that healthy beverages for pets are the next step."

Cott's move displays how companies are trying to grab a share of the U.S. pet industry. The American Pet Products Manufacturers Association expects Americans to spend about $43.4 billion on their pets in 2008, up from $41.2 billion in 2007. About $16.9 billion of that is expected to be spent on food. The emphasis on health and wellness products could entice more companies to try for a share of the pie.

Mainstream brands such as Procter & Gamble Co.'s Iams, Colgate- Palmolive Co.'s Hills brand and Nestle's Purina dominate the U.S. market for pet food and pet-care products, and a host of smaller, lesser-known brands are regularly introducing products for pets.

Cott says it spent nearly 18 months on research and development with veterinarians and food scientists to come up with the products designed to meet the specific nutritional needs of dogs. Its "Fortifido" line of fortified waters for dogs includes a peanut-butter flavored water that is fortified with calcium for healthy bones. Another is fortified with zinc for healthy skin, and there is even one pumped with spearmint for fresh breath.

Cott recently launched the products in some specialty stores and is trying for a wider national rollout. It also plans to make the products available online.

Cott has plenty of competition. Retailer PetSmart Inc.'s newer offerings include OVN, or Optimum Vitamin Nutrition, tablets that can be added to dog water. They come in three flavors -- chicken, chicken liver and bacon jerky -- and can be used to make gravy for dry food.

"The biggest thing in pet food at the moment is natural and organic, because it's been that way a couple years for humans," said Jim D'Aquila, managing director at financial advisory concern Mercanti Group, which specializes in consumer and wellness products. "They are adopting for their pets what they are adopting for themselves."

A recall of tainted pet food last year helped boost interest in organic and natural pet-food products, Mr. D'Aquila says. He says he believes that, ultimately, these trends in specialty products could lead to some consolidation in the pet-food industry, with private- equity players and mainstream companies buying niche brands.

Colgate-Palmolive, which makes toothpaste and soap, also has a flourishing pet-food business. Among its offerings is Science Diet Nature's Best, which includes real fruits, vegetables and grains, besides meat. Procter & Gamble sells Healthy Naturals, which include ingredients such as peas and carrots, many of which aren't traditional pet-food ingredients, a spokesman said.

The big question will be how higher-end pet products will fare in a weaker economy.

"The high-end food will continue to grow, [but] it won't grow at the same rate as it would in a healthy economy," Mr. D'Aquila said. "There is a subset of people there who are seeing this as an essential part of their pet's life." He says although owners might cut spending on accessories like fancy leashes, they are unlikely to crimp spending on food.

In the fourth quarter, Pet-Smart's earnings were hurt by weaker consumer spending, but the company said pet "parents" weren't trading down on food, despite economic pressures.

Write to Anjali Cordeiro at anjali.cordeiro@dowjones.com

Copyright 2008 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Rachel's Democracy & Health News highlights the connections between issues that are often considered separately or not at all.

The natural world is deteriorating and human health is declining because those who make the important decisions aren't the ones who bear the brunt. Our purpose is to connect the dots between human health, the destruction of nature, the decline of community, the rise of economic insecurity and inequalities, growing stress among workers and families, and the crippling legacies of patriarchy, intolerance, and racial injustice that allow us to be divided and therefore ruled by the few.

In a democracy, there are no more fundamental questions than, "Who gets to decide?" And, "How DO the few control the many, and what might be done about it?"

Rachel's Democracy and Health News is published as often as necessary to provide readers with up-to-date coverage of the subject.

Editors:

Peter Montague - peter@rachel.org

Tim Montague - tim@rachel.org

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

To start your own free Email subscription to Rachel's Democracy & Health News send a blank Email to: rachel-subscribe@pplist.net

In response, you will receive an Email asking you to confirm that you want to subscribe.

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Environmental Research Foundation

P.O. Box 160, New Brunswick, N.J. 08903

dhn@rachel.org

::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::